This story extracted from INFOTel news story that is linked here. Full credit for this article goes to Jenna Wheeler of INFOTel News.

KAMLOOPS – [July 22, 1983] the Tranquille psychiatric institution staff started a three-week sit in to protest the closure of the institution. For nearly 80 years, staff had lived on the land that was used first as a tuberculosis hospital, later becoming a psychiatric institution. Staff had formed relationships, families and made a community.

……

Before Europeans came to the area, First Nations people frequented the land for fishing and hunting.

After colonization, tuberculosis began ravaging Canadian communities, especially First Nations. In 1867, tuberculosis was the leading cause of death for people in Canada, according to the Canadian Public Health Association.

In the 1890s, two ranches belonging to the Fortune and Cooney families began taking in consumptives as boarders and allowed those infected with tuberculosis to live in small cabins or tents on the property and care for themselves as long as possible, according to a research paper by Glennis Zilm and Ethel Warbinek in 1994.

B.C. Society for the Prevention and Treatment of Consumption and Other Forms of Tuberculosis held its first meeting in January of 1904 to begin the plans and fundraising necessary to build an isolated tuberculosis hospital. According to the research paper by Zilm and Warbinek, they soon discovered a Kamloops property for sale, and after raising $58,000, bought 600 acres plus buildings from the family of early settler William Fortune. They also took over the lease for an additional 2,000 acres from the Dominion Government, and in 1922 bought the neighbouring 700-acre area from Charles Cooney.

The tuberculosis hospital was opened on November 28 of 1907, officially called the King Edward Memorial Sanatorium. At the time, the patients were kept in the original structures, but the demand for more spaces led to an almost constant state of construction. By 1910, the hospital could accommodate 49 patients and employed 4 nurses and 12 attendants, according to Zilm and Warbinek. Eventually, the sanatorium had 360 beds, according to the Tranquille Sanatorium Collection by Robb Gilbert.

[the site included many access tunnels] ……the tunnels, …. were mostly used to transport laundry and other goods.

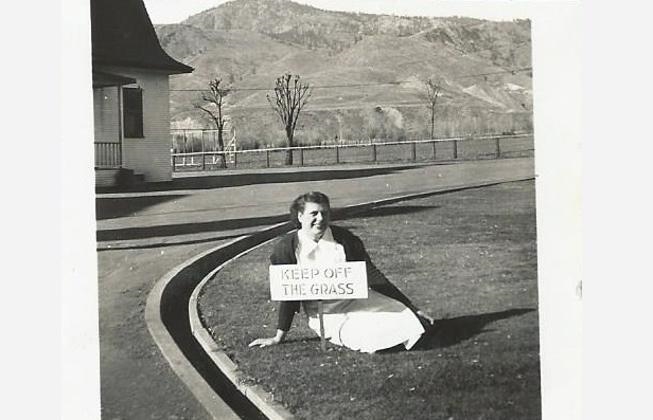

The property included Alexandra Ranch, which used to grow food and raise animals for the sanatorium patients, staff and to sell to the public. The farm grew and became a source of revenue through meat, dairy, and vegetables. The farm continued to operate even after the closure of the sanatorium. There was a newspaper, the Tranquillian, which was run by patients. Many of the staff lived on-site and formed relationships, and started families, with the children living there attending a small schoolhouse.

At the time, the hospital focused on preventing the spread of infection and taught self-care. A strict regimen of rest, healthy foods, and fresh air helped to treat those infected. The patients were kept in open-air verandas, and nurses who tended to them on winter mornings reported seeing their faces covered with frost.

About half of those admitted to the sanatorium paid for their own fees. Back then it cost around $55 dollars per month, and the average stay was for 200 days, according to Zilm and Warbinek.

In the early 1900s, approximately 1 in 7 of the populations of the world had died from the disease, but many of those estimates are based on the white population only, leading to much contemplation. Although

First Nations peoples made up only 3.7 percent of the provincial population in 1935, 32 percent of deaths from the disease were in the First Nation population, according to a report to the Canadian Tuberculosis Association.

The older buildings were torn down and replaced throughout the years. Construction continued while the sanatoriums population continued to grow, with many World War One soldiers returning with the disease.

When anti-tuberculosis drugs were introduced in the late 1940s, the dynamics of the hospital changed greatly.

Sanatoriums soon became unnecessary, and the hospital closed in 1958.

After the sanatorium closed, the province used the property as an institution for people with mental disabilities and illnesses. Information, including the official name of the institution, isn’t in the Kamloops archives collections. The province, responsible for operations of the institution, keeps all the archives in Victoria.

According to newspaper articles, the institution was better than others such as Glendale and Woodlands, but still, some believed patients had lost many of their rights.

At a time, patients were not allowed to open their own mail and they did unpaid work, which was seen as a therapeutic practice, according to a newspaper article in the Kamloops archives. The article states food, clothes, money, matches, and other items couldn’t be directly given to them by visitors.

An announcement was made that the institution would soon be obsolete, much to the dismay of the staff who called it home. According to Alan Garr, a reporter with the Vancouver Province, on July 19, 1983, 40 union workers of the 650 staff protested the closure, occupying the buildings for three weeks, with the numbers growing. The 324 patients still at the centre were transferred to community care, family homes, or other institutions. According to one article in the BCMHP News, there were 55 patients who were not considered able to return to the general population and were moved to Glendale, which brought about protests from families wanting to keep their loved ones close by.

After the closure, the location briefly became a detention centre for young offenders, according to an article in the Vancouver Sun.

In September of 1991, the Ministry of Land and Parks accepted an $8 million offer for the land. According to a release by the ministry, it was bought by an Italian developer, Giovanni Camporese, president of A&A Foods. He hoped to make the site into a destination site for tourists. It stated he planned to have lodging, a marina, and golf course, and commercial space. His idea turned to dust, but not before painting some of the buildings with murals.

“There is a mural painted on one of our buildings and when we did some research, we found out it was one of the towers from the cathedral in Padova,” McLeod says. “He renamed the site Padova because that’s where he was from originally.”

The city of Padova claims to be the oldest city in northern Italy. The escape room is focused on why somebody would paint a mural of the ancient city.

Today, the murals still stand, as do some of the buildings that served purposes for the sanatorium. The tours and tunnel escape rooms set up by Tranquille Farm Fresh honour the history of the land before colonization, during the tuberculosis epidemic, and through to the potential development project by Campese.

Trespassing is strictly forbidden, but you can visit the area by checking out events or booking a visit.

Recent Comments